A little irritability is normal — but here’s when it becomes a problem. Most of us have felt that flash of anger that seems to come out of nowhere. It might be sparked by a curt work email, a chatbot that refuses to help, dirty dishes left in the sink, or traffic grinding to a halt when you’re already late. These moments can trigger reactions that feel bigger than the situation itself — snapping at someone you love or leaning on the car horn a bit too long. During stressful periods, like the holidays, these outbursts can feel even more common.

At its core, irritability is an increased tendency toward anger, often triggered when things don’t go as planned or when we feel blocked or threatened. And if you experience it, you’re far from alone. A large 2024 U.S. survey of nearly 43,000 adults found that people rated their average irritability at 13.6 on a scale where 5 meant “never irritable” and 30 meant “irritable all the time.” The takeaway? Feeling irritable is extremely common — and often completely normal.

When Irritability Becomes a Burden

Problems arise when irritability stops being occasional and starts shaping daily life. Some people feel perpetually on edge, snapping easily or experiencing frequent and intense anger outbursts. According to Roy Perlis of Massachusetts General Hospital, irritability becomes concerning when it causes significant distress or interferes with normal functioning.

In clinical practice, he says, people report irritability just as often as they complain about anxiety or depression. A key warning sign is regret — frequently thinking, “I wish I hadn’t said that” or “I wish I hadn’t reacted that way.” When anger begins to damage relationships or spill into interactions with coworkers or strangers, it may be time to take it seriously.

Clinical psychologist Maria Gröndal from the University of Gothenburg has seen how distressing this can be in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). In the days before menstruation, intense irritability can lead to arguments at home or difficulty concentrating at work — even when the person tries hard to hold their temper in check.

The Biological Roots of Irritation

Irritability isn’t just a human quirk; it’s deeply rooted in biology. Neuroscientist Wan-Ling Tseng at Yale School of Medicine studies this by deliberately frustrating mice. When rodents expect a reward and don’t get it, they press levers harder and longer — much like humans jabbing an elevator button that won’t respond. These frustrated mice also show more aggression, mirroring human behavior.

Such findings suggest irritability may have evolved as a survival mechanism, motivating action when needs aren’t met. Still, what’s adaptive in small doses can become harmful when it dominates daily life.

What’s Happening in the Brain?

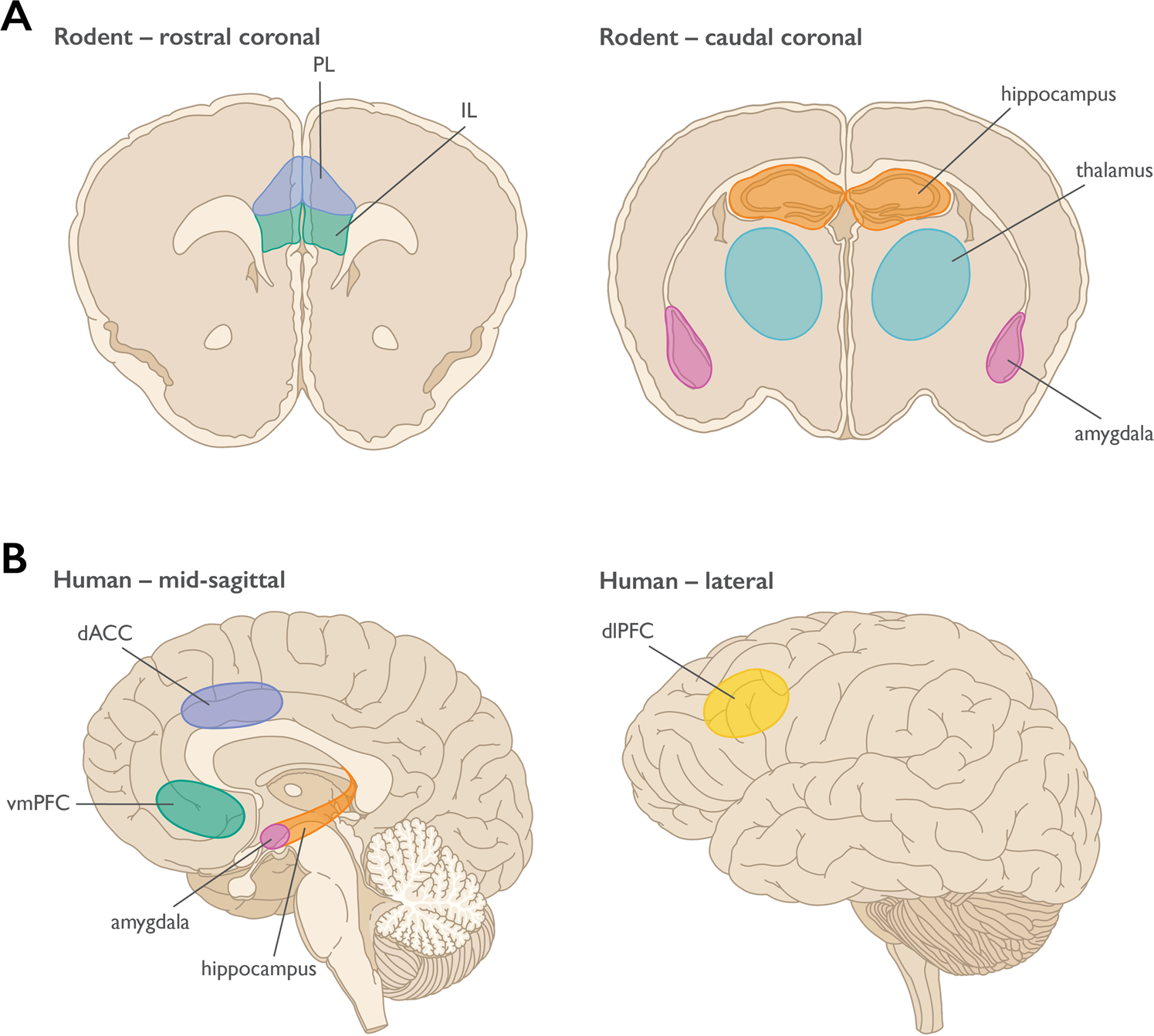

Research in children and teens offers clues about why some people are more prone to extreme irritability. Studies show that brain systems involved in reward and threat processing behave differently in highly irritable individuals. When frustrated, these brains show heightened activity in the striatum, a reward-related region, and unusual responses in areas responsible for focus and self-control. The amygdala — the brain’s threat detector — also tends to be more reactive.

Psychiatrist Manish Jha of UT Southwestern Medical Center notes that adult brains appear to involve the same circuits. Irritability, he explains, is often like a fever — a sign that something in the brain or body is out of balance.

It frequently accompanies conditions such as depression, anxiety, ADHD, bipolar disorder, and trauma-related disorders. Hormonal shifts, including those before menopause, can also play a role. Importantly, frequent irritability has been linked to an increased risk of suicidal thoughts, making it a crucial signal clinicians watch closely.

Still, irritability doesn’t always point to a diagnosable condition. Sometimes it’s influenced by temperament or everyday stressors like poor sleep, hunger, illness, pain, loneliness, quitting smoking — or even excessive social media use.

Finding Relief and Regaining Control

The good news is that problematic irritability is treatable. Mental health professionals often start by addressing underlying conditions. Treating depression or anxiety, for example, frequently reduces irritability as well. Certain antidepressants have also been shown to lower anger and even reduce suicidal thoughts.

Therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy help people recognize early signs of anger and respond in healthier ways. Newer approaches are emerging too: researchers are testing oxytocin nasal sprays, brain stimulation techniques, and digital tools that encourage self-monitoring.

Behavioral scientist Olivia Metcalf from the University of Melbourne found that simple self-awareness can make a big difference. In her research, trauma survivors who regularly checked in with their emotions and physical signals — like muscle tension or a racing heart — significantly reduced their anger over time.

Checking in with yourself can be as simple as asking: Am I clenching my jaw? Holding tension in my shoulders? Feeling tightness in my chest? Pairing this awareness with basics like adequate sleep, regular meals, and stress management can go a long way.

A Final Takeaway

Science makes one thing clear: being irritable doesn’t make you a bad person. As Perlis puts it, irritability isn’t a character flaw — it’s a state that can be understood and managed. A little irritability is normal — but here’s when it becomes a problem: when it takes over your days, strains your relationships, or leaves you feeling out of control. With awareness, support, and sometimes professional help, it’s possible to turn down the volume on anger and regain emotional balance.