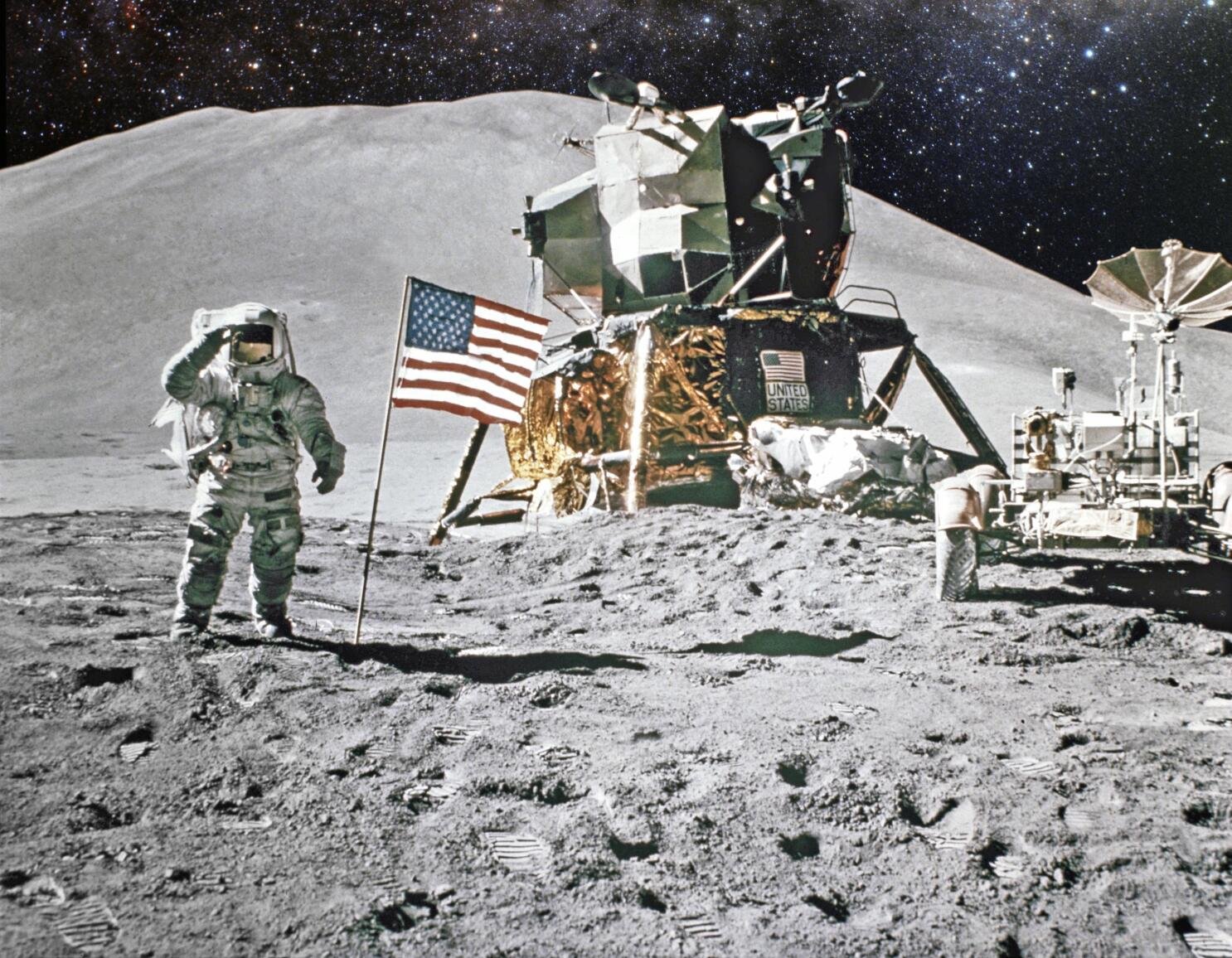

More than half a century has passed since a human last walked on the Moon. The long gap between Apollo and today’s Artemis era raises a compelling question: Why have humans not returned to the Moon for more than 50 years? The answer lies in a complex mix of politics, funding, technology, changing priorities, and evolving goals for space exploration.

The Last Footprints on Lunar Soil

On December 14, 1972, Apollo 17 commander Gene Cernan delivered an emotional farewell before leaving the Moon. He expressed hope that humanity would one day return in peace and unity. At the time, several future Apollo missions had already been canceled due to budget cuts, but few imagined that his words would remain the last spoken by a human on the lunar surface for decades.

Today, NASA’s Artemis program aims to restart human exploration of the Moon. Missions such as Artemis II will circle the Moon before future flights attempt landings. Still, the long delay highlights just how difficult returning has been.

Politics and Funding: The Biggest Barrier

The primary reason behind the long absence is not a lack of interest or capability—it’s the absence of sustained political commitment.

Human spaceflight programs require enormous funding, long-term planning, and consistent national support. However, space priorities have repeatedly shifted with changes in political leadership. Over the decades, administrations have alternated between focusing on the Moon, Mars, space stations, or asteroid missions.

Because lunar programs take many years and billions of dollars to complete, even a single policy change can cancel years of progress. This stop-and-start cycle prevented any long-term lunar initiative from reaching completion until recently.

The Challenge of Distance and Risk

Even with political support, lunar missions remain extremely difficult.

The Moon is about 400,000 kilometers away, and landing safely is far from routine—many robotic attempts by various countries have failed. Building the rockets, spacecraft, and life-support systems required for human missions takes decades of engineering and tens of billions of dollars.

NASA’s current Artemis architecture—including the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft—represents more than 20 years of development. Returning humans safely is not simply a repeat of Apollo; it requires modern safety standards, reliability, and advanced systems.

Why Apollo Can’t Just Be Recreated

It might seem logical to rebuild Apollo-era technology, but that isn’t practical. The industrial supply chains, specialized manufacturing techniques, and skilled workforce from the 1960s no longer exist.

Although modern computers are vastly more powerful, human spaceflight remains complex, dangerous, and expensive. Unlike consumer technology, spacecraft systems must undergo years of testing and certification because failure is not an option.

Today’s Orion spacecraft is far more advanced than Apollo’s command module, offering greater computing power, more living space, improved life-support systems, and privacy features suitable for diverse crews.

A New Goal: Staying, Not Just Visiting

Apollo’s missions were designed as short-term demonstrations—often described as “flags and footprints.” Artemis has a very different purpose.

NASA now aims to build long-term infrastructure around and on the Moon, including:

Sustainable landing systems

Lunar habitats

The Gateway space station in lunar orbit

Resource utilization, such as potential water ice at the poles

The goal is to create a lasting human presence that can support future deep-space missions, including journeys to Mars.

The Rise of Commercial and International Partnerships

Another major difference from the Apollo era is collaboration.

NASA now works closely with private companies such as SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Boeing, treating them as partners and service providers. This commercial ecosystem helps reduce costs and accelerate development.

International cooperation is also expanding. Through the Artemis Accords, more than 60 nations have agreed to principles for peaceful and sustainable lunar exploration. Returning to the Moon is no longer a single-country effort—it’s becoming a global endeavor.

Geopolitics and the New Space Race

Competition still plays a role. During Apollo, the United States raced against the Soviet Union. Today, China’s growing space ambitions—including plans for a crewed lunar mission around 2030—have renewed strategic urgency.

However, modern space agencies are balancing competition with safety. Past tragedies, including Apollo 1, Challenger, and Columbia, have led to a more cautious and methodical approach.

Why the Return Is Finally Happening

After decades of shifting priorities, the key difference today is continuity. The Artemis program has survived multiple administrations and now benefits from:

Stable political backing

Commercial partnerships

International cooperation

Mature technology and infrastructure

These factors are finally aligning to make a sustainable return possible.

Looking Ahead

The long gap since Apollo wasn’t due to a lack of ambition—it reflected the enormous cost, risk, and complexity of human space exploration, combined with changing political and strategic priorities.